Are we all Salesmen?

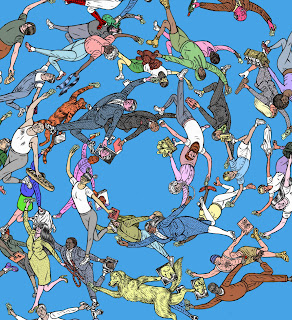

Everything Is for Sale Now. Even Us.

The constant pressure to sell

ourselves on every possible platform has produced its own brand of modern

anxiety.

By Ruth Whippman

Ms. Whippman is the author of

“America the Anxious: Why Our Search for Happiness Is Driving Us Crazy and How

to Find It for Real.”

Nov. 24, 2018

There is something about the

consumer madness of the holiday season that makes me think of my friend

Rebecca’s mother. When I was in middle school, she had a side hustle selling

acrylic-rhinestone bug brooches. The jewelry was hard to move on its merits —

even for the 1980s it was staggeringly ugly. But what she lacked in salable

product, she made up for in sheer selling stamina. Every sleepover, school fair

or birthday party, out would come the tray of bejeweled grasshoppers and stag

beetles, glinting with Reagan-era menace.

Presumably someone was making money

from this venture — some proto-Trump barking orders from his tax haven — but it

certainly didn’t seem to be Rebecca’s mother, whose sales pitches took on an

ever more shrill note of desperation.

Soon she had given up even the basic

social pretense that we might actually want the brooches. The laws of supply

and demand morphed seamlessly into the laws of guilt and obligation, and then

into the laws of outright malice, mirroring the trajectory of capitalism

itself.

At that time, when naked hawking to

your friends was still considered an etiquette blunder, the sales pitches by

Rebecca’s mother felt embarrassing — as gaudy and threatening to the social

ecosystem as a purple rhinestone daddy longlegs. But 30 years later, at the

height of the gig economy, when the foundation of working life has apparently

become selling your friends things they don’t want, I look back to that raw

need in Rebecca’s mother’s eyes with something terrifyingly approaching

recognition.

As a writer, I am part of the 35 percent of the American work force that now

works freelance in some capacity, either as a main source of income or as some

kind of side hustle. This number is growing constantly — 94 percent of the new jobs created in the last

decade or so were freelance or contract-based.

When we think “gig economy,” we tend

to picture an Uber driver or a TaskRabbit tasker rather than a lawyer or a

doctor, but in reality, this scrappy economic model — grubbing around for work,

all big dreams and bad health insurance — will soon catch up with the bulk of

America’s middle class.

Martin

New York8h

ago

Times Pick

The "gig economy" is simply the economy based on

the powerful using the rest of us purely as tools for its profit, without

minding the social consequences. It's a world where working people have to

compete for the privilege of serving their economic masters, and be ready to

thrown away when someone or some technology is more useful than they. This

economy was created deliberately, with the destruction of unions, with deregulation

& privatization, with the corruption of politics by money, and the

replacement of legislators by lobbyists. It thrives on our feelings of

powerlessness.

Major

companies now outsource many of even their most skilled jobs, ditching their

in-house lawyers and I.T. support teams in favor of on-demand contractors, paid

by the hour. More than 18 million Americans are now involved in

some kind of direct sales or multilevel marketing scheme, shelling out hundreds

of dollars on vitamins or juicers or leggings, then frantically attempting to

recoup the money by flogging them to friends and neighbors. Economists predict that by 2027, gig workers of

varying descriptions will make up more than half of the work force. An

estimated 47 percent of millennials already work in this way.

It certainly feels familiar. Almost everyone I know now

has some kind of hustle, whether job, hobby, or side or vanity project. Share

my blog post, buy my book, click on my link, follow me on Instagram, visit my

Etsy shop, donate to my Kickstarter, crowdfund my heart surgery. It’s as though

we are all working in Walmart on an endless Black Friday of the soul.

Being sold to can be socially awkward, for sure, but when

it comes to corrosive self-doubt, being the seller is a thousand times worse.

The constant curation of a salable self demanded by the new economy can be a

special hellspring of anxiety.

Like many modern workers, I find

that only a small percentage of my job is now actually doing my job. The rest

is performing a million acts of unpaid micro-labor that can easily add up to a

full-time job in itself. Tweeting and sharing and schmoozing and blogging.

Liking and commenting on others’ tweets and shares and schmoozes and blogs.

Ambivalently “maintaining a presence on social media,” attempting to sell a

semi-fictional, much more appealing version of myself in the vain hope that

this might somehow help me sell some actual stuff at some unspecified future

time.

The trick of doing this well, of

course, is to act as if you aren’t doing it at all — as if this is simply how

you like to unwind in the evening, by sharing your views on pasta sauce with

your 567,000 followers. Seeing the slick charm of successful online

“influencers” spurs me to download e-courses on how to “crack Instagram” or

“develop my personal brand story.” But as soon as I hand over my credit card

details, I am flooded with vague self-disgust. I instantly abandon the courses

and revert to my usual business model — badgering and guilting my friends

across a range of online platforms, employing the personal brand story of

“pleeeeeeeeeeaassssee.”

As my friend Helena (Buy her young

adult novel! Available on Amazon!) puts it, buying, promoting or sharing your

friend’s “thing” is now a tax payable for modern friendship. But this

expectation becomes its own monster. I find myself auditing my friends’ loyalty

based on their efforts. Who bought it? Who shared it on Facebook? Was it a

share from the heart, or a “duty share” — with that telltale, torturous

phrasing that squeaks past the minimum social requirement but deftly dissociates

the sharer from the product: “My friend wrote a book — I haven’t read it, but

maybe you should.”

In this cutthroat human marketplace,

we are worth only as much as the sum of our metrics, so checking those metrics

can become obsessive. What’s my Amazon ranking? How many likes? How many

retweets? How many followers? (The word “followers” is in itself a clear

indicator of something psychologically unhealthy going on — the standard term

for the people we now spend the bulk of our time with sounds less like a functioning

human relationship than the P.R. materials of the Branch Davidians.)

Of course a fair chunk of this mass

selling frenzy is motivated by money. With a collapsing middle class, as well

as close to zero job security and none of the benefits associated with it,

self-marketing has become, for many, a necessity in order to eat.

But what’s more peculiar is just how

imperfectly all this correlates with financial need or even greed. The sad

truth is that many of us would probably make more money stacking shelves or

working at the drive-through than selling our “thing.” The real prize is

deeper, more existential. What this is really about, for many of us, is a

roaring black hole of psychological need.

After a couple of decades of

constant advice to “follow our passions” and “live our dreams,” for a certain

type of relatively privileged modern freelancer, nothing less than total

self-actualization at work now seems enough. But this leaves us with an angsty

mismatch between personal expectation and economic reality. So we shackle our

self-worth to the success of these projects — the book or blog post or range of

crocheted stuffed penguins becomes a proxy for our very soul. In the new

economy you can be your own boss and your own ugly bug brooch.

Kudos to whichever neoliberal

masterminds came up with this system. They sell this infinitely seductive

torture to us as “flexible working” or “being the C.E.O. of You!” and we jump

at it, salivating, because on its best days, the freelance life really can be

all of that.

But as long as we are happy to be

paid for our labor in psychological rather than financial rewards, those at the

top are delighted to comply. While we grub and scrabble and claw at one another

chasing these tiny pellets of self-esteem, the bug-brooch barons still pocket

the actual cash.

This is the future, and research

suggests that it’s a rat race that is already taking a severe toll on our

psyches. A 2017 study suggests that this trend toward

increasingly market-driven human interaction is making us paranoid, jittery,

self-critical and judgmental.

Analyzing data from the

Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale from 1989 to 2016, the study’s authors

found a surprisingly large increase over this period in three distinct types of

perfectionism: “Self-orientated,” whereby we hold ourselves to increasingly

unrealistic standards and judge ourselves harshly when we fail to meet them;

“socially prescribed,” in which we are convinced that other people judge us

harshly; and “other-orientated,” in which we get our revenge by judging them

just as harshly. These elements of perfectionism positively correlate with

mental health problems, including anxiety, depression and even suicide, which

are also on the rise.

The authors describe this new-normal

mind-set as a “sense of self overwhelmed by pathological worry and a fear of

negative social evaluation.” Hmm. Maybe I should make that my personal brand

story.

Ruth Whippman is the author of

“America the Anxious: Why Our Search for Happiness Is Driving Us Crazy and How

to Find It for Real.”

A version of this article appears in

print on Nov. 24, 2018, on Page SR1 of the New York edition with the headline:

We’re All in Sales Now. Order Reprints | Today’s

Paper | Subscribe

Reader Comments:

Katherine Goss

Floral Park, NY8h

ago

Times Pick

The advice to “follow your bliss”

and “chase your dream” was always terrible. We all want a job that brings some

degree of status, satisfaction, and maybe makes the world better, but a job is

first and foremost a way to support yourself (and maybe a family). Rather than

“follow your passion” I suggest that people determine what they’re good at that

translates into a job and BRING passion to that work. You’d be surprised how

satisfying a simple job well done is...and a salary and health insurance are

pretty compelling. Of course, this isn’t to let soul sucking capitalism off the

hook. And a few lucky souls will always manage to find financial success in the

creative world, and we’re all richer for it. But if you need to earn a living,

then there’s no shame in a day job.

wynterstail

WNY8h

ago

Times Pick

My daughter is a hairdresser, with a

small salon of her own. After all the overhead involved (rent, shampoo, coffee,

etc.) she takes home about $15,000 a year. This is why at 38 she still lives

with me. All of her friends seem to have a conglomeration of "little"

jobs--bartending two nights a week, selling Mary Kay, and house sitter. I've

pointed out that even a full time job at McDonald's would earn more and at

least have some benefits. But she's become accustomed to being her own boss and

sees anything less as a failure.

Martin

New York8h

ago

Times Pick

The "gig economy" is

simply the economy based on the powerful using the rest of us purely as tools

for its profit, without minding the social consequences. It's a world where

working people have to compete for the privilege of serving their economic

masters, and be ready to thrown away when someone or some technology is more

useful than they. This economy was created deliberately, with the destruction

of unions, with deregulation & privatization, with the corruption of

politics by money, and the replacement of legislators by lobbyists. It thrives

on our feelings of powerlessness.

Jean Campbell

Tucson, AZ3h

ago

Times Pick

The term "gig economy" is

misleading and vaguely insulting and this article nails why it's so pernicious.

Of course "gig" makes it seem as if we are out there pursuing our

dreams of being a dancer, photographer, actor. "Side hustle"

insinuates we are just a resourceful group of happy freelancers having fun and

pursuing passions, completely the opposite of what most "gig" jobs

are: low-paying and requiring little skill or expertise. Uber, Rover,

NutriSystem. The economy is fast turning into a pyramid scheme that requires

constant renegotiating, anchored to a tenuous online reality. And the reasons

for "gigs" and "hustles" are because a huge percent of

regular jobs are either unbearable, humiliating, or don't pay.

Rick Gage

Mt Dora7h

ago

Times Pick

Your view of the new "gig"

economy and it's relation to our physical and mental well being makes me realize

that "Medicare for all" is the only viable way to move forward with

healthcare in this nation. Especially mental healthcare. If we're all gonna be

for sale, we'll want to make sure we're in good working order.

New York Times Opinion Article: Everything

Is for Sale Now. Even Us.

1. Who is the writer of the article and

what has she written before?

2. When was this article written?

3. Why does the

madness of the holiday season make him think about his friend’s mother?

4. What was noteworthy about Rebecca’s

mother? What desperate thing did she do?

5. “But

30 years later, at the height of the gig economy, when the foundation of

working life has apparently become selling your friends things they don’t want,

I look back to that raw need in Rebecca’s mother’s eyes with something

terrifyingly approaching recognition.” What is the writer saying about life and work today?

6. What does it mean to work

“freelance” or “contract based”? What might be the perks and the disadvantages

of doing this kind of work?

7. What percentage of the “new” jobs

that have appeared in the last decade have been freelance or contract based?

8. What percentage of the American

workforce is employed in this kind of labor?

9. How would you define “gig economy”

in relation to this article?

10. ____________

predict that by____________ , gig workers of varying descriptions will

make up more than _______ of the work

force. An estimated ____________ percent of _______________ already work in this way.

11. According to the writer of the

article, almost everyone she knows has a what? WHat examples does she give?

12. The writer writes, “It’s as though we are all working in Walmart on an

endless Black Friday of the soul. Being sold to can be socially awkward, for

sure, but when it comes to corrosive self-doubt, being the seller is a thousand

times worse. The constant curation of a salable self demanded by the new

economy can be a special hellspring of anxiety.” How could this description of

workers today help you understand Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman?

13. What kind of work is the writer

referring to when she mentions “performing a million

acts of unpaid micro-labor?”

14. Where does social media come into

play regarding all of this?

15. “In this cutthroat human marketplace, we are worth only

as much as the sum of our metrics, so checking those metrics can become_____________.

What’s my Amazon______________? How many__________? How many ______________?

How many____________? (The word “____________s” is in itself a clear indicator

of something psychologically unhealthy going on…”

16. According to the writer, what is

motivating all of this?

17. What this is really about, for many of us, is a

roaring black hole of______________

______________.

18. Why is this a “thing?” What

motivated this? The writer says a couple of decades of “what” exactly motivated

this?

19. But this

leaves us with an angsty mismatch between personal _______________ and economic______________. So we shackle our

_____________ to the success of these projects — the book or blog post or range

of crocheted stuffed penguins becomes a proxy for our very soul. How does this

sound like a modern day Willy Loman?

20. How do the “masterminds” sell this

kind of economic model for people? What kind of words do they use in their

propaganda to get people enticed to do this?

21. This is the ____________, and research suggests that

it’s a ________ ___________that is already taking a severe toll on our

_____________. A 2017 study suggests that this trend toward

increasingly market-driven human interaction is making us ____________________,

__________________, ___________________ and ____________________.

22. List the three types of

perfectionism observed to exist because of all this:

23. Define “self- oriented”

perfectionism?

24. Define “socially prescribed”

perfectionism?

25. Define “other-oriented”

perfectionism?

26. These elements of perfectionism

unfortunately cause “what” that can also be seen in Willy Loman’s character in Death

of a Salesman?

27. What do authors describe this

new-normal mind-set as?

28. Would you say everybody in

modern-day America is susceptible of becoming a “salesman?” Who are not?

Comments

Post a Comment